Imagine two researchers working with the same dataset to answer the same high-stakes policy question: Does a new vocational training program helps unemployed adults earn more? Both are well-trained. Both follow standard practices. Both make what they believe are reasonable, defensible choices in their models.

Yet when they present their results, the headline numbers don’t match. One reports a strong positive effect, the other finds only a modest improvement, and a third version of the analysis—perhaps run later for validation—suggests that the effect may be negligible. What changed? The data didn’t. The policy didn’t. The only differences were the countless small choices each researcher made while building their statistical model.

This situation is more common than we might hope. In research and policy analysis, small, seemingly sensible decisions—adding or removing a control variable, defining a key concept slightly differently, or analyzing a specific subgroup—can tilt the findings in one direction or another. These aren’t mistakes or manipulation; they are inherent, everyday parts of the analytical workflow. But they lead to a troubling reality: even reasonable, well-intentioned analyses of the same data can produce divergent answers to the same question.

In earlier posts, we explored how foundational assumptions—like the shape of a relationship (functional form) or the type of statistical distribution—shape the answers we get from data. Those discussions showed why models are not neutral mirrors of reality. In this post, we will explore additional scenarios where analytical choices directly alter the estimated impact of a policy.

To make these concepts concrete, we will use simulated data from a hypothetical vocational training program for unemployed adults to demonstrate exactly how the program’s estimated impact changes with each modeling choice that any analyst could make. Simulated data and code available here.

What is Model Dependence?

Model dependence means that our conclusions can change depending on the specific statistical model we choose. When results shift noticeably under different, reasonable modeling decisions, we say the analysis exhibits high model dependence.

This might sound abstract, but the idea is familiar in everyday life. Consider viewing a landscape through different camera lenses. A wide-angle lens captures the entire scene but can distort the edges. A telephoto lens reveals fine details but hides the broader context. A portrait lens sharpens the subject while softly blurring the background. Each lens offers a legitimate view of the same scene. None is objectively “wrong.” Yet each tells a subtly—or sometimes dramatically—different story about what matters. What you see depends entirely on the lens you use.

Statistical models are our analytical lenses. Each model we apply to a dataset is a choice about what to bring into focus, what to adjust for, and what to treat as background. Some lenses simplify complex relationships; others highlight intricate interactions. Some include many factors; others isolate a single relationship. These choices are not technical quirks; they are routine decisions about what to include, how to measure a variable, and which part of the data to analyze.

What Drives Model Dependence?

In the previous section, we established that statistical models are like lenses, each offering a different view of the same data. Now, we put that idea into practice. Using simulated data from a hypothetical vocational training program, we examine five common analytical choices that act as different “lenses.” For each, we will see how the estimated impact of the program shifts—sometimes dramatically.

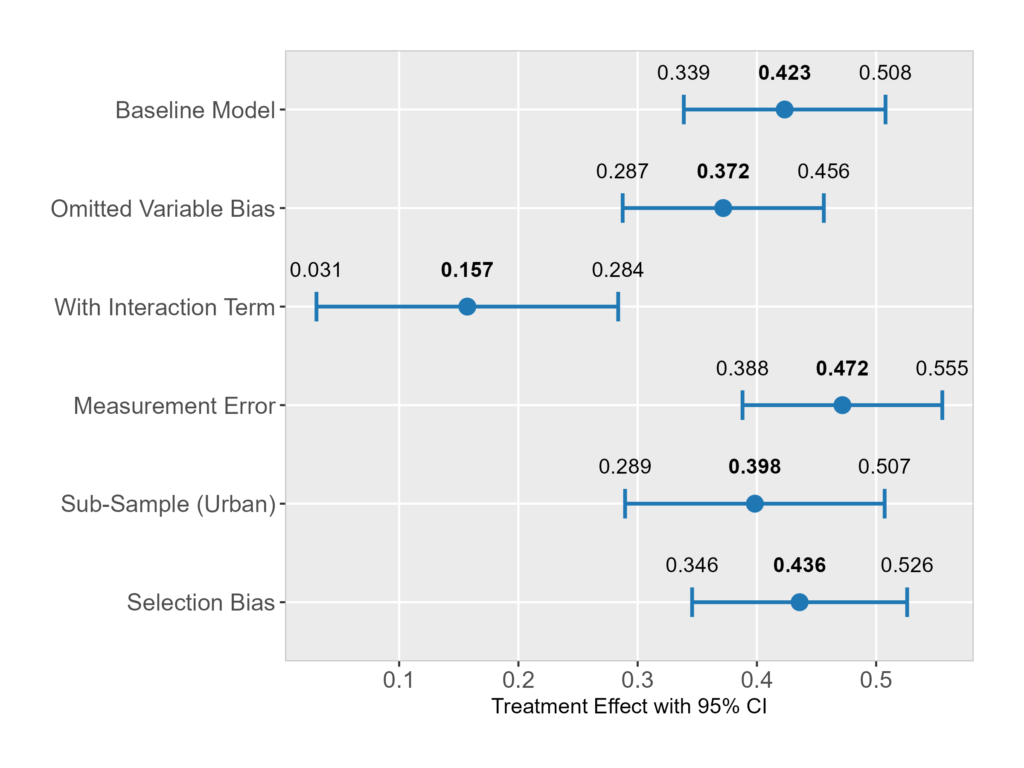

Our baseline model, which includes all critical control variables, shows the program increases monthly earnings by roughly 42%. This is our starting point, our clearest adjusted view. The figure below plots how this key result changes under five alternative modeling scenarios. A detailed table is also provided at the end of the post. Note that the outcome is log-monthly earnings, and for simplicity we describe changes in the treatment coefficient in percentage terms without converting the log values.

1. Omitted Variable Bias: When a Missing Factor Tilts the Story

The baseline estimate is 42%. But if we omit gender from the model, the estimate falls to 37%. Why? In our simulation, women are more likely to participate in the program but also tend to have lower pre-program earnings. By failing to account for gender, the model mistakenly attributes part of this pre-existing earnings gap to the program, making it look less effective. This is the classic omitted variable bias. It underscores why a deep understanding of the context—knowing what drives both program participation and the outcome—is non-negotiable. A disappointing evaluation result might stem from a missing variable, not a failed program.

2. Interaction Effects: When the “Average Effect” Hides Unequal Impact

What if the program does not work the same for everyone? When we allow the effect to differ by marital status, the story fractures. The “main” effect plummets to 16% because the average blends two very different realities: a massive effect for married adults and a modest one for unmarried adults. The 42% average was a statistical fiction. This warns us that relying solely on an average effect can be dangerously misleading. It can lead to funding broadly ineffective programs or failing to target resources where they have the highest return. Smart policy requires asking for whom a program works, not just if it works on average.

3. Measurement Error: When Data Look Similar but Behave Differently

Here, we swap a clean measure (true years of schooling) for a noisy one (self-reported schooling). The result? The estimated program effect jumps to 47%. The mismeasured variable fails to fully adjust for the confounding role of education, leaving residual bias that inflates the estimate. This illustrates that data quality is not just an academic concern—it is the foundation of credible evidence. Basing policy on poorly measured confounders can lead to overly optimistic (or pessimistic) conclusions.

4. Sample Composition: When Results Reflect Who Is Included

What happens if we evaluate the program using only data from urban areas? The estimated effect shifts to 40%. While the change is not extreme, it is meaningful. The urban effect does not equal the effect in the full population. This means that evidence from one setting may not travel neatly to another. A pilot program’s success in urban centers does not guarantee the same results in rural areas. Policymakers must be cautious about generalizing findings from one subgroup to an entire population.

5. Selection into the Analysis Sample: When Who Shows Up Shapes the Estimate

Finally, let’s analyze only the individuals who end up in our dataset—a group where selection favors treated individuals with higher earnings potential. In this selected sample, the estimate rises to 44%. The program looks better because our “lens” is focused on its most successful participants. This is classic selection bias. It warns us that incomplete datasets—due to survey non-response, administrative gaps, or voluntary participation—can create a distorted, overly rosy picture of a program’s effectiveness.

Across all five examples, a single lesson emerges: reasonable, defensible choices in model specification can lead to meaningfully different conclusions from the same data. This is model dependence in action. It is not a sign of error or manipulation, but a fundamental characteristic of data analysis. Ultimately, robust conclusions arise not from any single model, but from deliberately viewing the data through many lenses.

Conclusion

Our journey through the simulated data reveals a fundamental truth: evidence is not found—it is shaped by the modeling choices we make. Researchers can reach different conclusions from the same data, not because one is right and another is wrong, but because each looks through a different analytical lens. This is why humility is not just virtuous in empirical work; it is essential.

This echoes George Box’s famous reminder: “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” In policy, usefulness does not mean certainty. It means clarity about our assumptions, transparency about the alternatives we tested, and an honest assessment of how robust our conclusions remain across different plausible models.

With that mindset, the goal shifts. We stop searching for the single “correct” model and start asking a better question: What does the data consistently tell us, no matter how we look at it?

As you move forward—designing evaluations, interpreting evidence, or making decisions—carry this lesson with you. Stay curious, seek multiple perspectives, and maintain a sweet skepticism toward any result that hinges on a single, fragile model. Durable insights emerge not from one lens, but from the convergence of many.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (Vocational Training) | 0.423*** | 0.372*** | 0.157** | 0.472*** | 0.398*** | 0.436*** |

| (0.043) | (0.043) | (0.065) | (0.043) | (0.056) | (0.046) | |

| Log of Baseline Monthly Earning | 0.321*** | 0.330*** | 0.322*** | 0.312*** | 0.344*** | 0.316*** |

| (0.039) | (0.040) | (0.039) | (0.040) | (0.047) | (0.041) | |

| Schooling Years (Actual) | 0.048*** | 0.049*** | 0.049*** | 0.051*** | 0.048*** | |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.004) | ||

| Gender (Female = 1) | -0.150*** | -0.151*** | -0.154*** | -0.137*** | -0.151*** | |

| (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.024) | (0.028) | (0.024) | ||

| Marital Status (Married = 1) | 0.335*** | 0.330*** | -0.032 | 0.341*** | 0.339*** | 0.331*** |

| (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.078) | (0.024) | (0.028) | (0.025) | |

| Treatment X Married | 0.406*** | |||||

| (0.082) | ||||||

| Place of Residence (Urban = 1) | 0.085*** | 0.082*** | 0.086+++ | 0.072*** | 0.076*** | |

| (0.025) | (0.026) | (0.0025) | (0.026) | (0.026) | ||

| Schooling Years (Self-Reported) | 0.024*** | |||||

| (0.003) | ||||||

| Observations | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 1402 | 1875 |

| R-Squared | 0.240 | 0.224 | 0.250 | 0.203 | 0.238 | 0.239 |

Table 1: Treatment effects under various model specifications. Note: Monthly earning (in log scale) is the outcome variable. Column (1) is the baseline model. For comparison, we consider the baseline model as the best estimate of average effect in the population. Female indicator is omitted in column (2). Column (3) includes interaction between the treatment and married indicator. Column (4) uses self-reported schooling instead of actual schooling years. Column (5) is the analysis conducted among the sub-sample of urban adults, and column (6) is the sub-sample analysis conducted among those likely to be selected in the treatment. Robust standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1