It has been a while since my last post—since March, to be exact. Life threw me an unexpected challenge: a detached retina. The fix? Surgery where surgeons injected silicone oil into my eye to press the retina back into place. But the oil does not work magic on its own. For it to work, I had to maintain a face-down position for several hours each day. That way, gravity could help the oil push the retina against the back of the eye.

Sounds simple, right? Just face down for a while and let physics do its thing. It was not that simple. The instructions seemed straightforward at first—stay face-down for eight hours a day. But during follow-up visits, the recommendations began to vary. Some doctors suggested three hours might be sufficient; others proposed four. Some recommended splitting the time into shorter intervals. This inconsistency left me wondering: what is the actual relationship between the hours I spend face-down and the pressure on my retina? Does each additional hour contribute equally, or are there diminishing returns after a certain point? Could the pattern be nonlinear—something less obvious than a straight line?

I realized this question was about more than just my recovery. It is the same type of question researchers and policymakers wrestle with every day: determining how much of an intervention is enough. Whether it is the number of training hours in a job program, the dosage of a social policy, or time spent in post-surgical recovery, understanding the nature of these relationships is everything. In other words, it is all about understanding the functional form.

In this post, we will explore why getting the functional form right is critical for making sound decisions. I will use a hypothetical example of social programs to demonstrate how different modelling choices lead to different interpretations and policy implications. Along the way, we will discuss why it is risky to assume “more is always better” or that effects increase in a straight line.

What is Functional Form Assumption?

At its heart, every statistical model we fit is built on a guess about the shape of the relationship between our variables. This guess is the functional form assumption. For example, when we use a linear regression model, we assume that the effect of an independent variable (like training hours) on the outcome (like employment probability) is constant across all values. It draws a straight line through our data, implying that each additional hour of training provides the exact same boost in the probability of getting a job, whether it is the first hour or the hundredth.

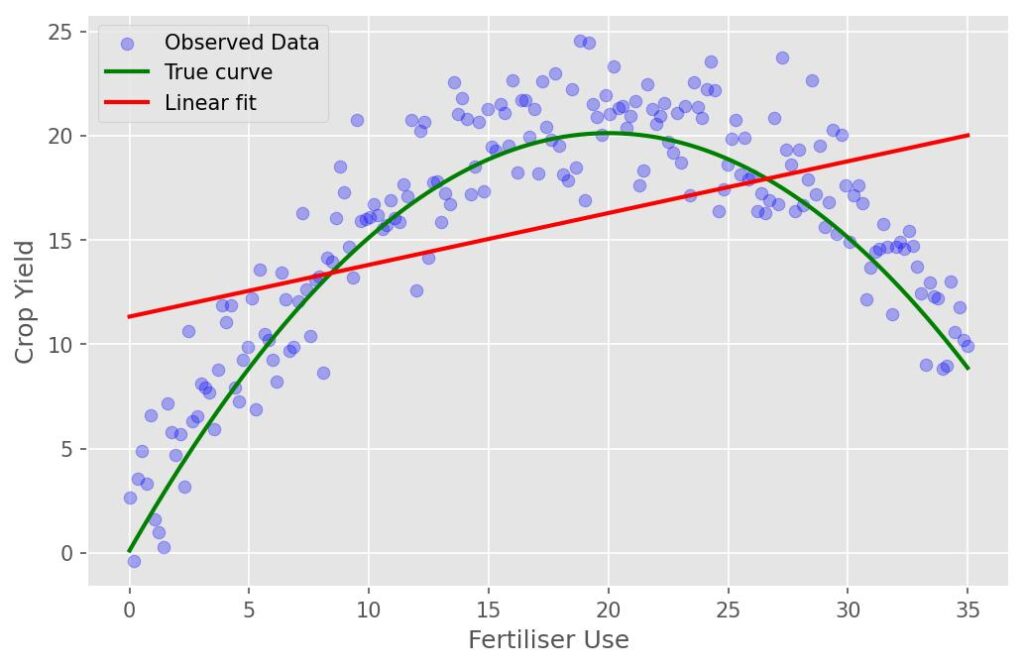

But reality is rarely so neat. Many relationships are not straight lines. They could be curved, have thresholds, or even plateau after a certain point. Think of fertilizer use in agriculture. A small dose may have no effect, an optimal dose provides maximum yield, and an excessive dose does not help the plants grow any taller. The relationship is profoundly non-linear, climbing and then curving downward (figure 1).

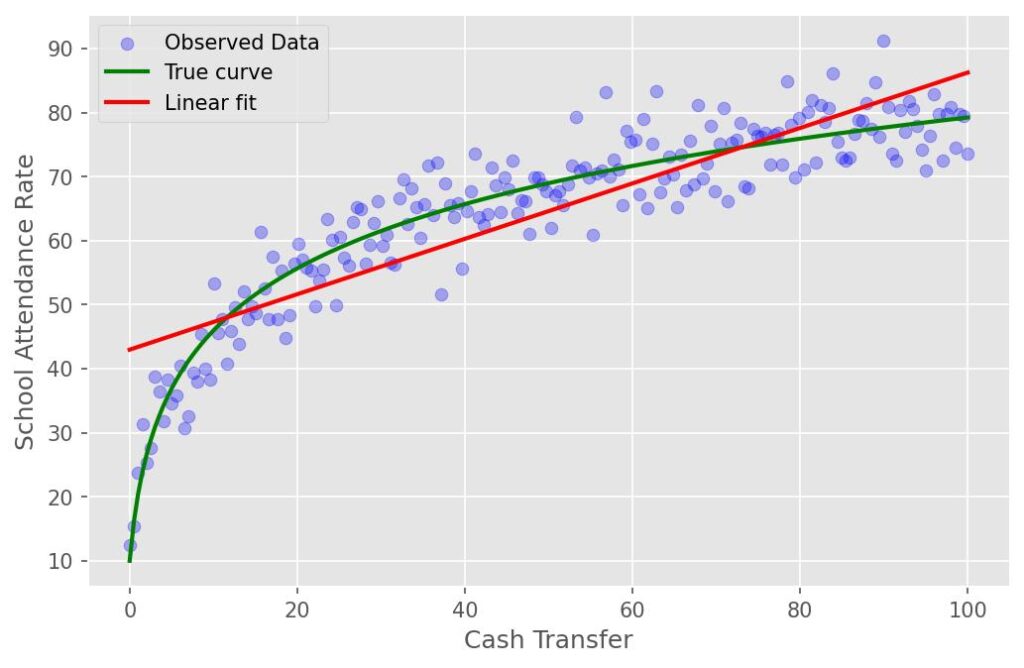

Or, consider a cash transfer programs. If we assume the relationship between transfer size and school attendance is linear, doubling the transfer should double the impact. But what if the real relationship shows diminishing returns? In that case, the relationship would look like a steep climb that gradually flattens out (figure 2). Doubling the transfer could cost twice as much while improving attendance only marginally.

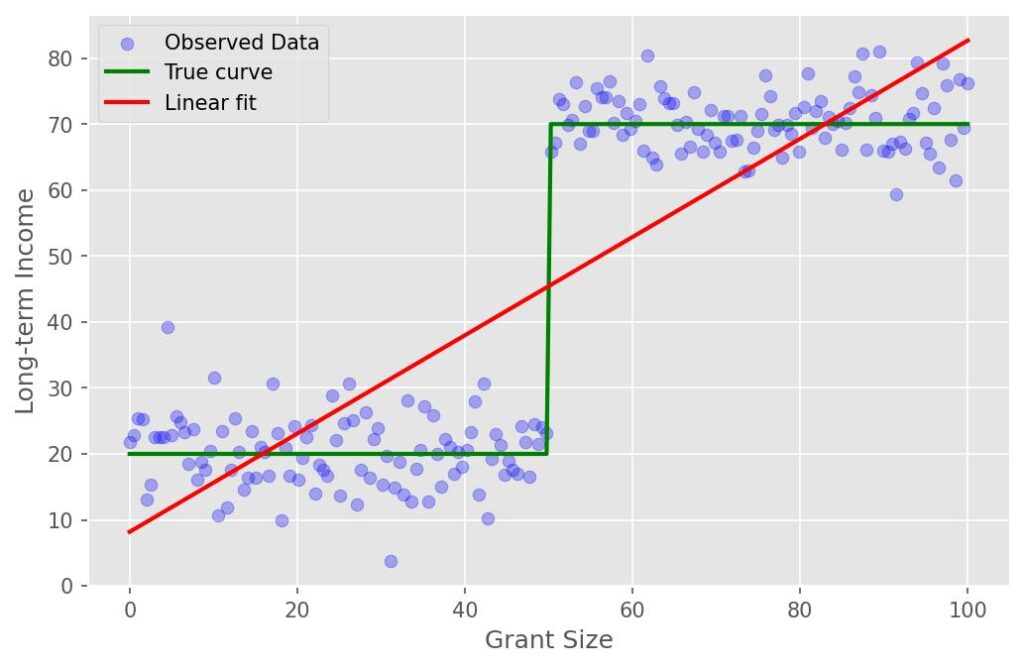

A different kind of non-linear relationship is the threshold effect. Imagine a program providing a one-time cash grant to aspiring entrepreneurs in extreme poverty. A very small grant might be used immediately for food, with no lasting impact on income. However, once the grant reaches a critical threshold—enough to purchase a sewing machine or inventory—it can catalyze a permanent shift out of poverty. The relationship between grant size and long-term income is not a straight line; it is flat, then it suddenly jumps (figure 3).

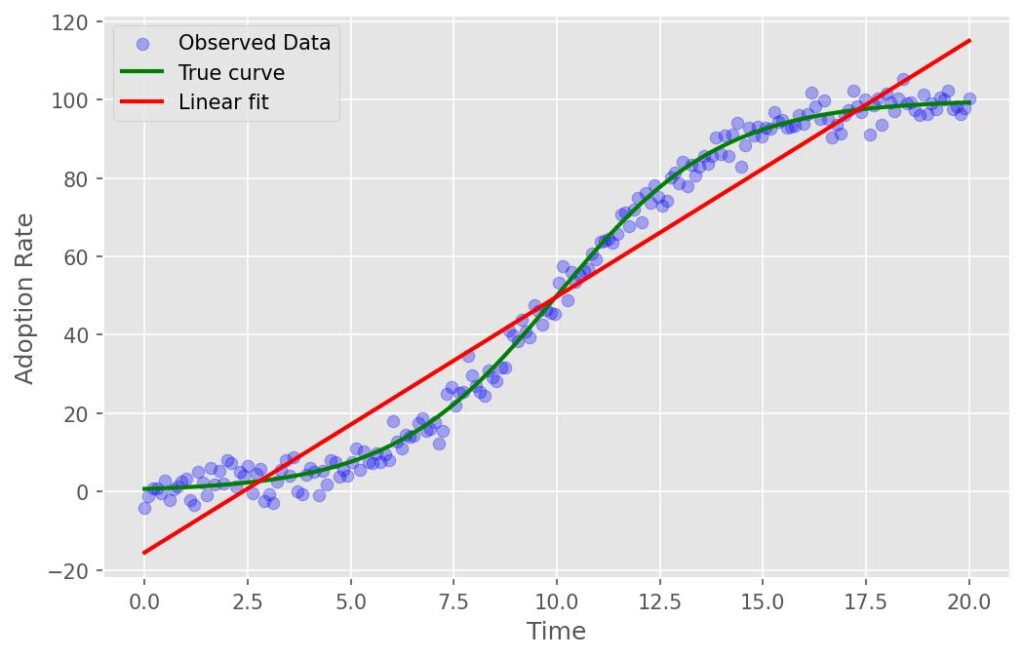

Similarly, consider the adoption of a new agricultural technology, like drought-resistant seeds. Initial adoption is slow (the flat part of the curve) as only the most risk-tolerant farmers try it. Then, as early adopters succeed, their peers rapidly follow suit through social networks, creating a period of steep, rapid adoption (the sharp upward slope). Finally, adoption plateaus (the flat top of the curve) once nearly everyone who is willing and able to use the technology has done so (figure 4).

Why Functional Form Matter for Policy and Practice?

The graphs above come from simple simulations to mimic different relationships common in social programs. A simple linear model was fitted to each scenario, and its predictions were compared to the true underlying pattern (simulated dataset available here). These patterns are not just math—they shape real policy outcomes. When decision-makers assume a straight-line relationship, they risk serious misinterpretations. Here is what that looks like with some concrete examples from the simulated data.

Take fertilizer use and crop yield. A linear model tells us that doubling fertilizer from 10 to 20 kg/ha will increase yields by about 2.48 units. But in reality, the gain could be 5 units—double the true benefit predicted by the linear model. That underestimation could discourage programs that promote moderate fertilizer use, even when such programs are highly effective. Now flip the problem. Consider a scenario with diminishing returns, such as increasing cash transfers from $50 to $100. A linear model predicts the benefit will rise by 21.64 units, when the true gain is only 10.25 units. That is an overestimation of 11.39 units, which could lead governments to overspend on larger transfers that barely move the needle.

Threshold effects tell another story. For a small grant program, doubling the grant from $25 to $50 might seem like a minor tweak. A linear model predicts an improvement of 18.62 units, but the real effect is a dramatic 50 units. Underestimating this jump could doom a program that simply needed a slightly bigger push to unlock life-changing benefits. Finally, technology adoption often follows an S-curve. Doubling the time from 5 to 10 years for a rollout might seem modest. A linear model predicts adoption will increase by 32.66 units, but the true jump is closer to 42.41 units. Linear thinking understates this dynamic surge.

| Policy Scenario | Linear Model (β₀, β₁) * | Doubling To | Linear Prediction | True Effect | Misinterpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fertilizer Use | (11.33, 0.25) | 10 to 20 kg/ha | 2.48 | 5.00 | Under by 2.52 |

| Cash Transfer Program | (42.97, 0.43) | $50 to $100 | 21.64 | 10.25 | Over by 11.39 |

| Small Grant Program | (8.18, 0.74) | $25 to $50 | 18.62 | 50.00 | Under by 31.38 |

| Technology Adoption | (-15.58, 6.53) | 5 to 10 years | 32.66 | 42.21 | Under by 9.75 |

*Coefficients are from a simple linear regression fitted to the simulated data.

Closing Thoughts

The gaps between prediction and reality are not trivial—they shape budgets, priorities, and lives. Misreading the functional form can mean under-funding what works, overspending on what does not, or abandoning programs that were just shy of a breakthrough. Understanding these curves is not academic hair-splitting; it is the difference between smart policy and costly mistakes. Just as my doctor might have benefited from thinking about functional forms, so can researchers and policymakers.

If you are a policymaker, ask whether your assumptions match reality. If you are a researcher, look closely at the shape of your data before drawing straight lines. The extra effort to question these assumptions can pay dividends in effectiveness and fairness.

In this post, we focused on parametric approaches—methods that impose a specific functional form, like linear or quadratic. But what happens when relationships are more complex? That is where non-parametric approaches come in. We will explore it in the next post.

On a personal note, my own journey is not over. In a week or so, I will undergo another surgery to remove the silicone oil from my eye and replace it with a gas bubble—another phase in the long recovery process. For the next couple of months, I will have time to rest and heal. Until then, I invite you to stay thoughtful about the functional form, both in your work and in life.